BIRTH OF A MOVEMENT

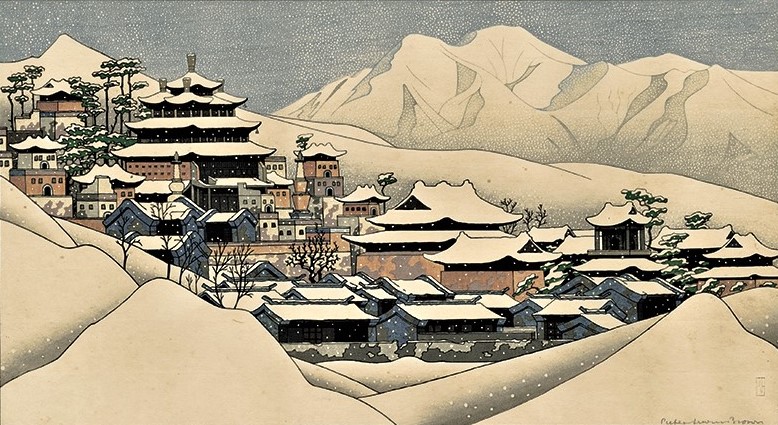

Only a few years after the forced opening of Japan, by Rear Admiral Matthew Perry's squadron, did Japanese art enter Europe. Decorative objects, furniture, fans, combs, parasols, kimonos and prints seduced the avant-garde of a bourgeoisie amazed by this still little-known civilization, just as aristocratic circles had been equally attracted in the 18th century by China.

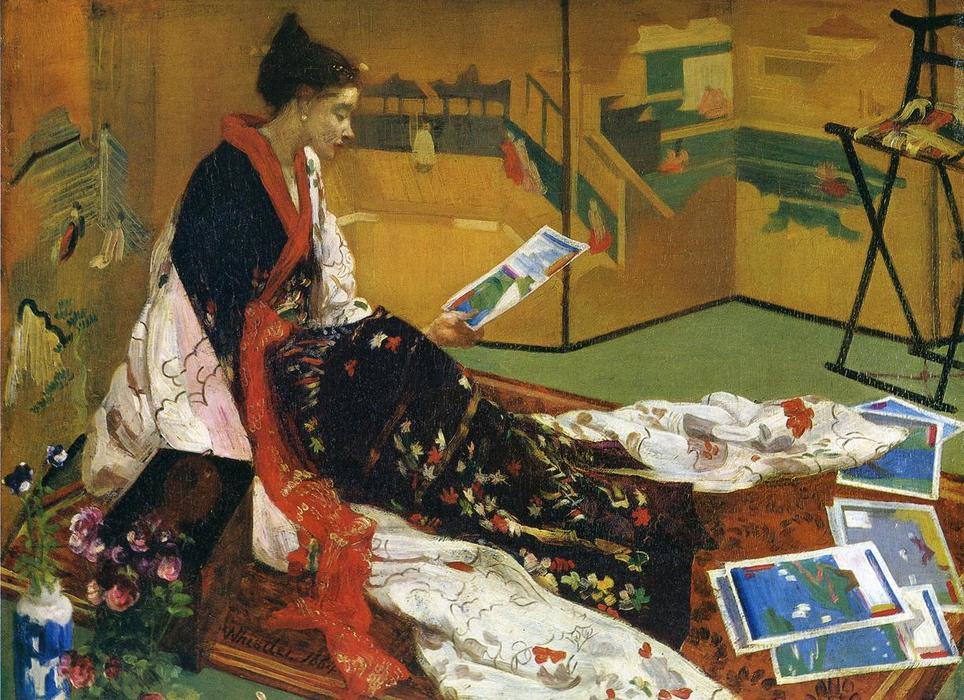

The British pictorial world reaped the first fruits of this. James Abbott McNeill Whistler, in order to deviate from the academicism still prevalent in London, was inspired by Japanese art to blaze a new path. In 1864, he painted his faithful model Jo, dressed in a kimono and surrounded by prints at the foot of a screen. Many paintings with the same inspiration accentuated the career of this inventive artist along with his students.

His friend, the Franco-British James Tissot, lived in Paris and was surrounded by Japanese objects offered by Prince Akitake who had come to represent the Emperor at the Universal Exhibition of 1867, where the Japanese pavilion was a revelation for many. He hence spiced his work with Japanese references.

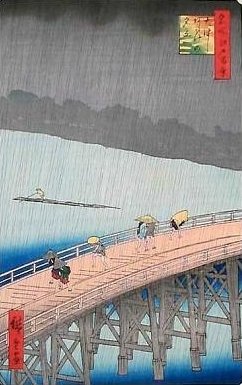

While these artists opened the way, they often limited themselves to creating an “ambience,” by including Japanese traditional costumes or objects in their paintings. Impressionism took a step further by drawing inspiration from ukiyo -e prints. These appeared in the West in the 1860s and quickly won the support of many artists who were amazed to discover what the Japanese novelist Asai Ryoi had described as early as 1661, "To live only for the present, to contemplate the moon, the snow, the cherry trees in flowers and autumn leaves, to love wine, women and songs, to let oneself be carried by the current of life like a water bottle : this is what we call the floating world."

The works of the end of the 18th and the beginning of the 19th century by Kiyonaga and Utamaro, followed by Hiroshige and Hokusai, had marked the golden age of this very specific art, and are to find once again, thanks to the West, a new youth.

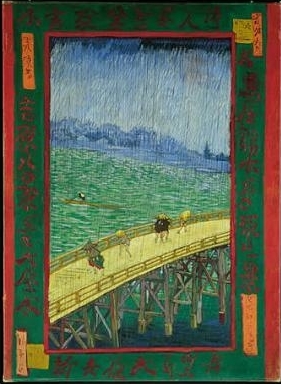

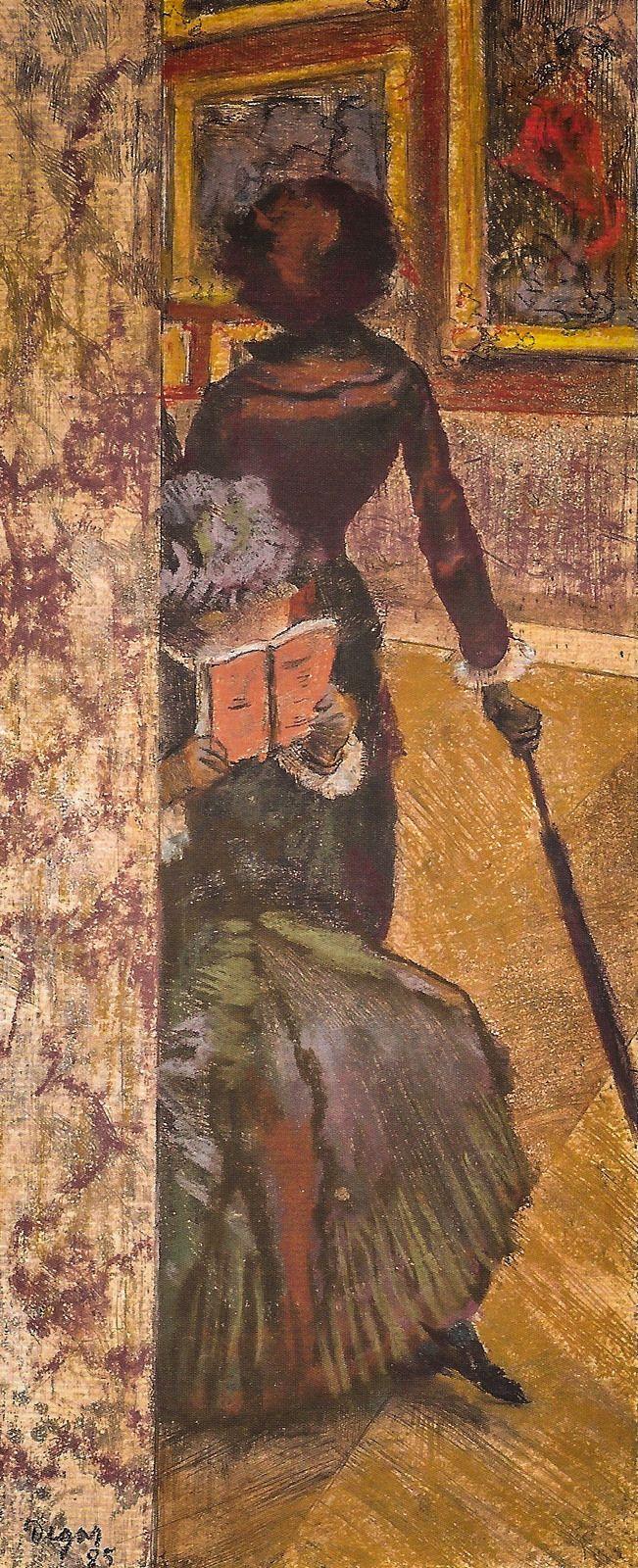

Impressionism takes hold of this breath coming from the Far East. Many paintings by Degas, Monet, Van Gogh, Gauguin, Picasso and others testify to the real discovery that Japanese art brings them in the colour and audacity of the compositions. Red, green, yellow, blue thus mingle in a natural harmony, the bursts of which make you forget the academicism and the halftone world of the first half of the century.

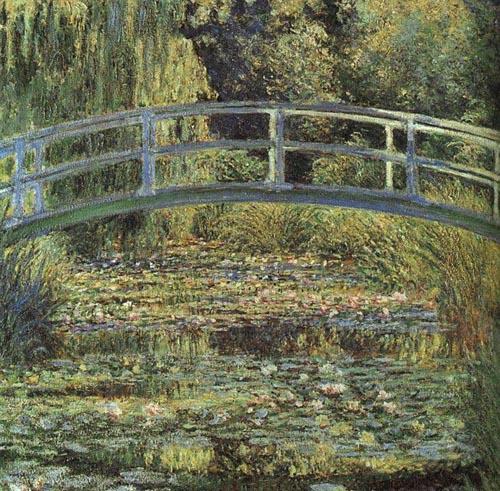

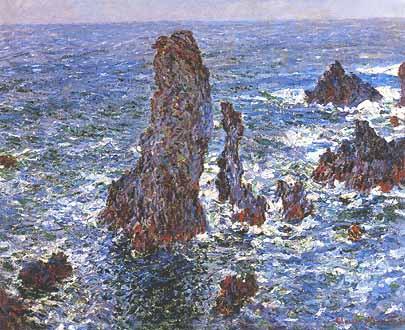

Claude Monet (1840-1926) was first tempted by the exoticism brought to his early days by Japonism by painting his wife dressed in a kimono against a background of fans. But he gradually allowed himself to be "impressed" by the "images of the floating world" to bring out a new spectacle of nature through interplay of mixed colours as evidenced by the pyramids of Port-Coton de Belle-Île. This is where he painted the Japanese bridge in the garden of his house in Giverny where today's visitor discover, in his intact salons, his entire collection of Japanese prints exactly where he had wanted to display them.

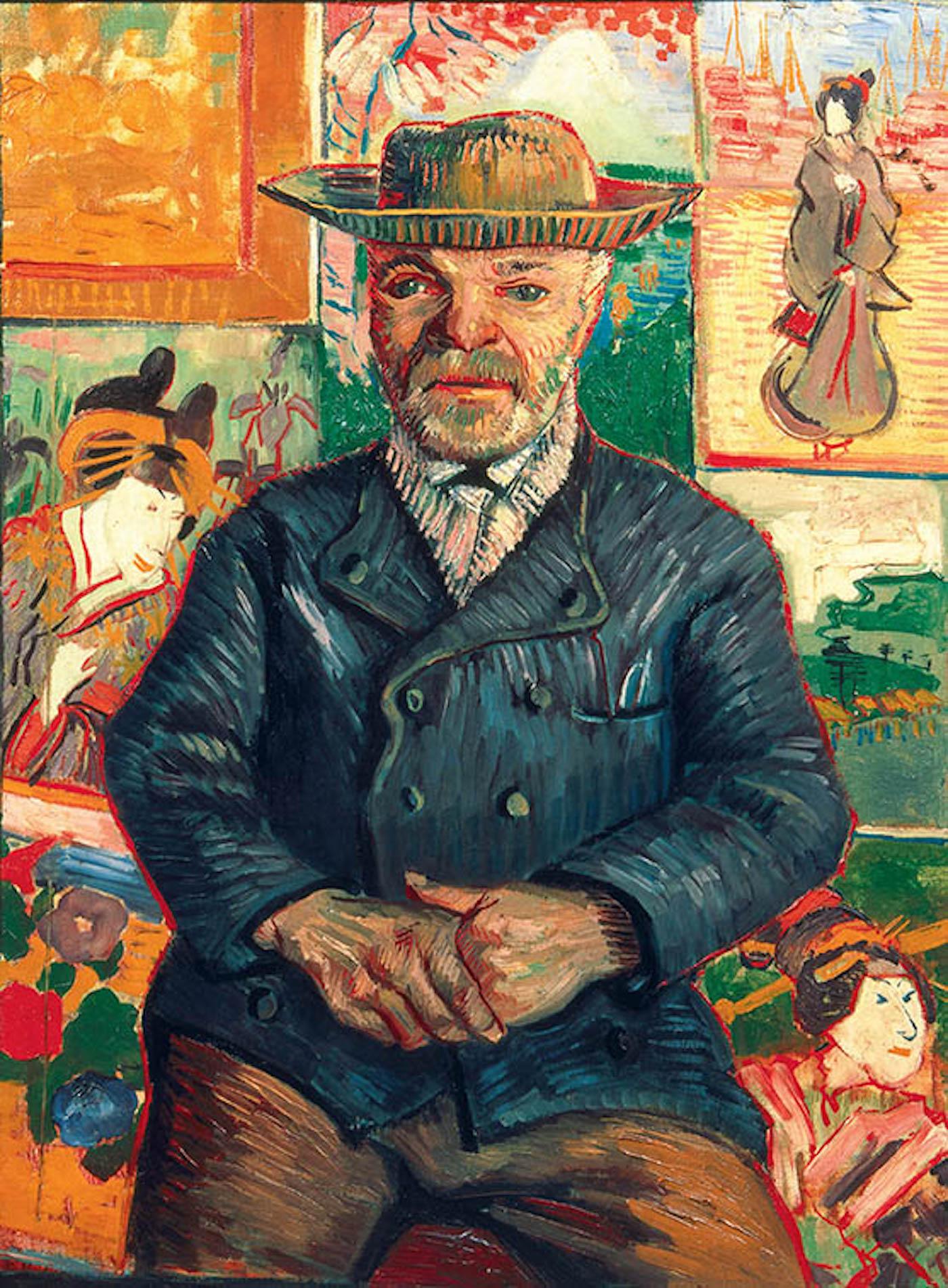

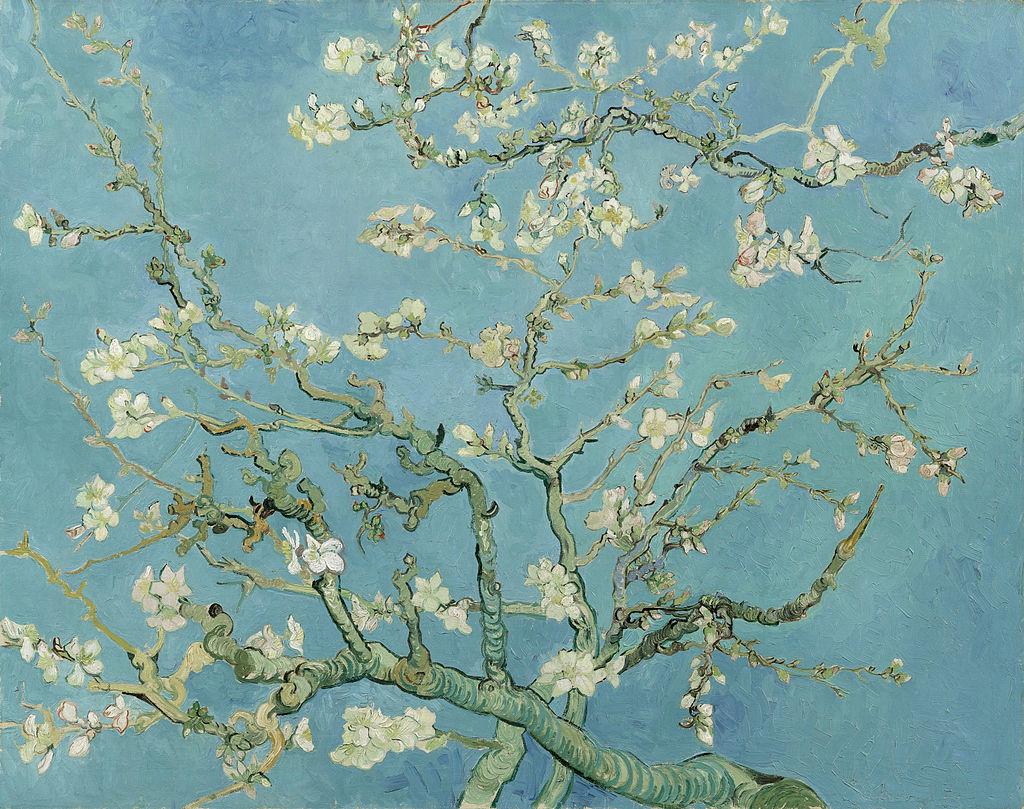

The link with Japan is also close with Vincent Van Gogh (1853-1890) who practiced pastiche prints (The Bridge in the Rain), introduced them to portraits (Father Tanguy) and recreated the atmospheric flower of the empire of the rising sun (The Almond Trees in Bloom).

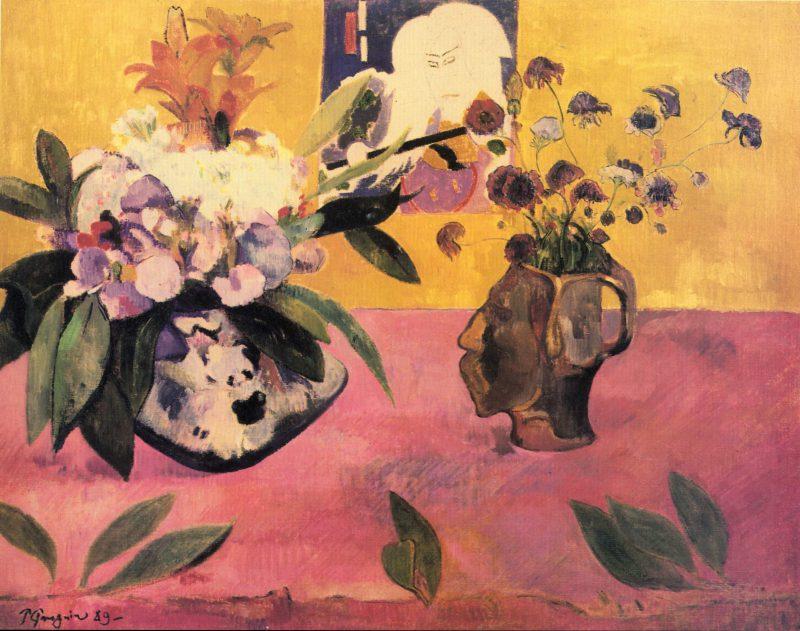

Paul Gauguin (1848-1903) also collected prints and played with the picturesque, as depicted in his still life decorated with a Japanese warrior. However he quickly goes beyond this stage by inventing a painting style where the marked lines and invigorated colours are particularly reminiscent of the partitioning Japanese woodblock prints. Gauguin will also be the first to no longer be satisfied with the European spectacle and to seek, even beyond the Far East, other worlds in the depths of the diversity of cultures.

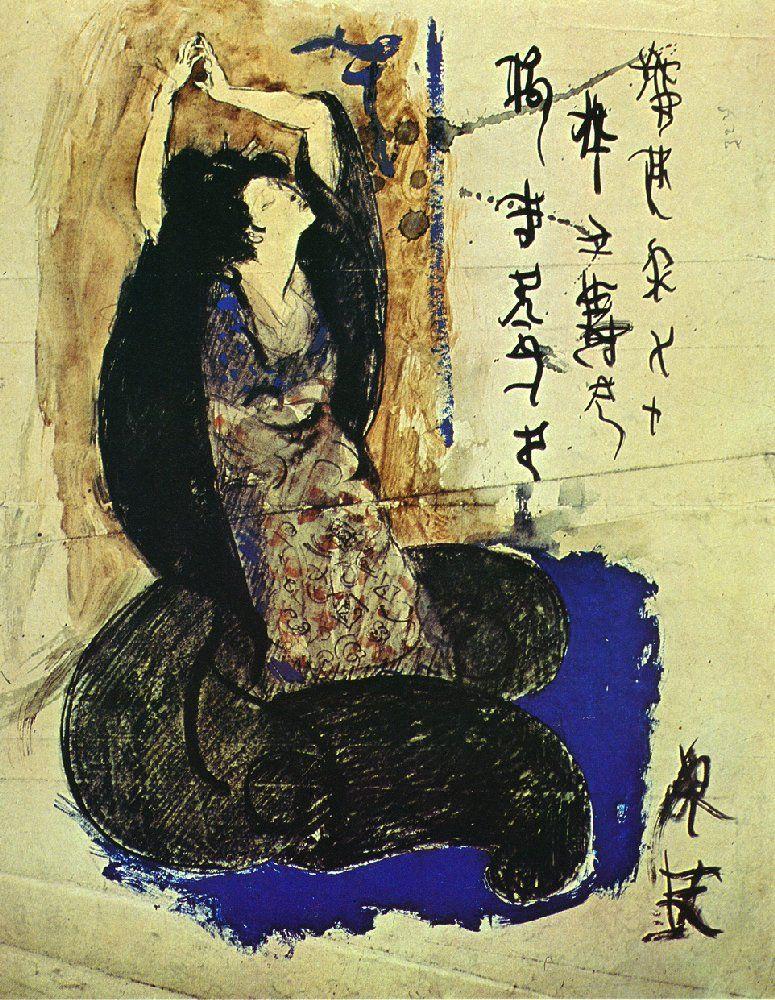

Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) went even further. Equally curious in his early youth of the oriental mystery embodied by the famous dancer of the time, Sada Yakko, he began building his universe by retaining only the geometry of his erotic prints from Japan.

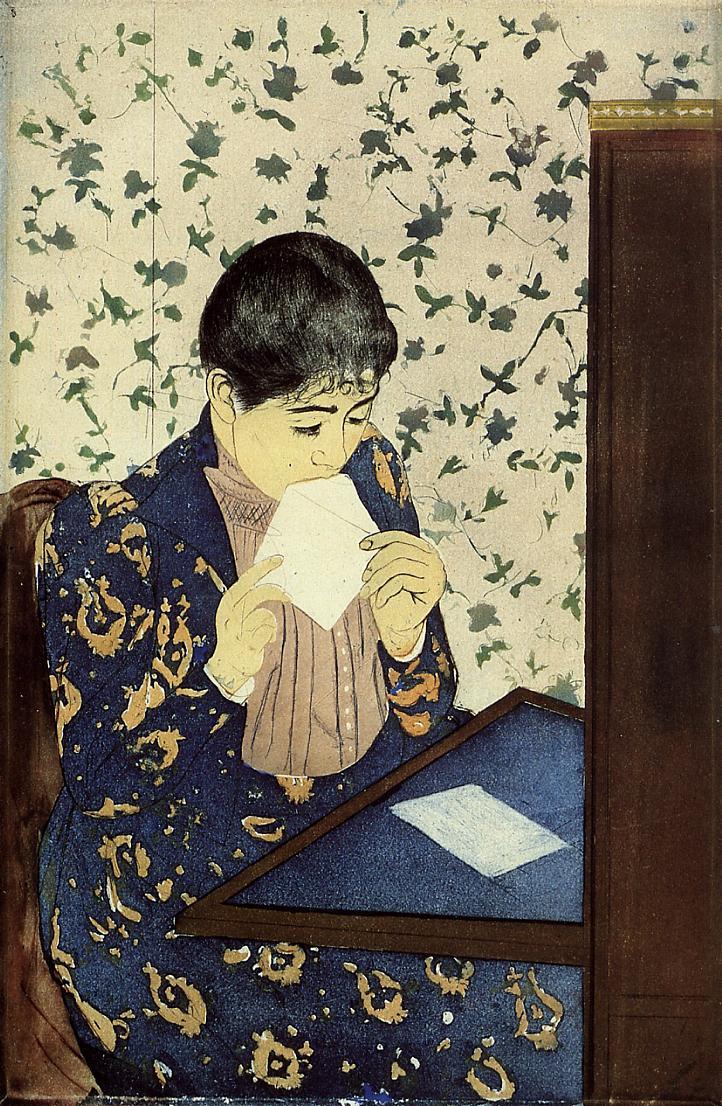

A particular mention should be made to Mary Cassat (1844-1926) who inaugurated a line of women seeking in the far East a domain where their modernity and sensitivity accompanied the search for their independence.

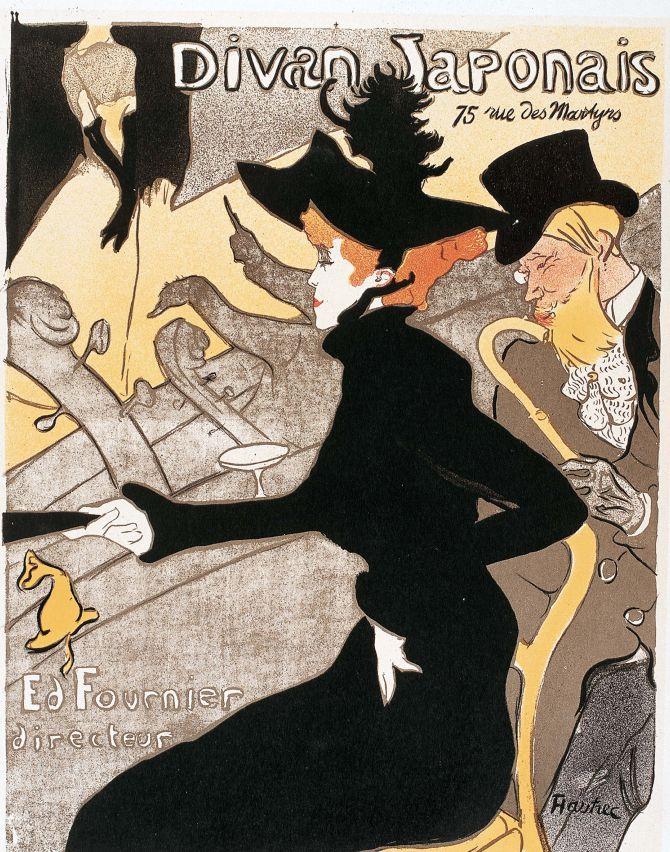

At the end of the 19th century, the Japanese wave accompanied the beginnings of a new technique: lithography and a new mode of communication: the poster. Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864-1901) is the emblematic figure of this expression, with a promising bright future and he will find in Japanese prints a source of inspiration that will influence the entire next generation.

Bibliography :

- Lionel Lambourne, Japonisme, échanges culturels entre le Japon et l’Occident, Phaidon, 2006

- Gabriele Fahr-Becker, L’estampe Japonaise, Benedikt Taschen, 1994

- Collectif, Van Gogh et le Japon, Actes Sud, 2018

- Collectif, Van Gogh, rêves de Japon, Pinacothèque de Paris, 2012

- Museu Picasso de Barcelona, Secret images : Picasso and the Japanese erotic print, Thames & Hudson, 2010

- Danièle Devynck, Toulouse-Lautrec et le japonisme, Musée d’Albi, 1991