PAUL JACOULET (1896-1960)

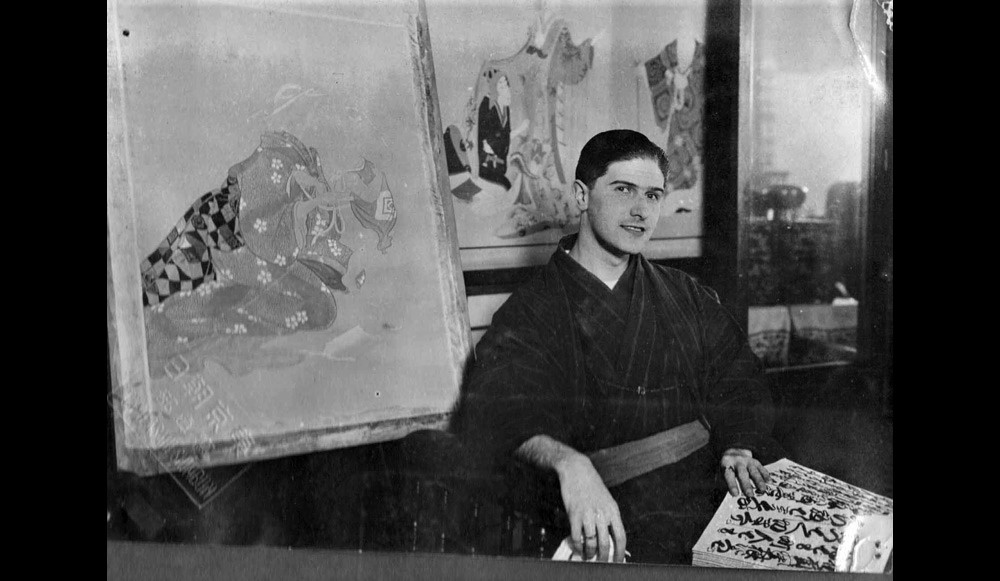

Born in Paris in 1896, Paul Jacoulet followed his mother three years later to Japan where she joined her husband, appointed to the University of Tokyo. He spent his whole life in Japan until his death in 1960. His exceptional personality is the fruit of both the care taken by his parents to give him a very thorough artistic education, in painting and music, and the quality of his schooling by the Japanese educational system.

Still a child, his father took him to Paris to discover the Impressionists and the masterpieces of Western painting. Back in Tokyo, he followed the teaching of great Japanese masters : Seiki Kuroda and Keichiro Kume who taught him oil painting ; Terukata Ikeda and his wife Shoen who introduced him to the prints of the "floating world", the ukiyo-e, and made him discover the work of Utamaro ; and at the same time, he studied Japanese classical music, learning the Gidayu (sung story) and the shamisen (three-stringed lute).

His father was mobilized in France during The First World War. Seriously wounded, he returned to Tokyo in difficult conditions and died in 1921. As a consequence, her mother had to come back to France. Alone, he had to work for ten years as a translator at the French Embassy in Tokyo. The ambassador, Paul Claudel, did not notice this young man who took advantage of the slightest free time to visit Japanese artistic circles and led a bohemian life. He continued to practice music and watercolor, to collect butterflies and prints and to learn the technique of wood engraving.

His mother returned in 1929. She moved to Korea with her new Japanese husband, who was a professor at the University of Seoul. From then on, she provided her son with the support that enabled him to devote himself entirely to painting. For ten years, he traveled intensely, finding in the discovery and observation of new countries, cultures and characters the subjects of what will become his work. Pacific Islands, Korea, Manchuria were then territories under Japanese control which he visited on many occasions and there form faithful friendships. In particular, from 1931 he became friends with two young Korean brothers, Jean-Baptiste and Louis Rah, who became his assistants, sharing his life until his end (in 1951, he adopted Thérèse, daughter of Jean -Baptiste).

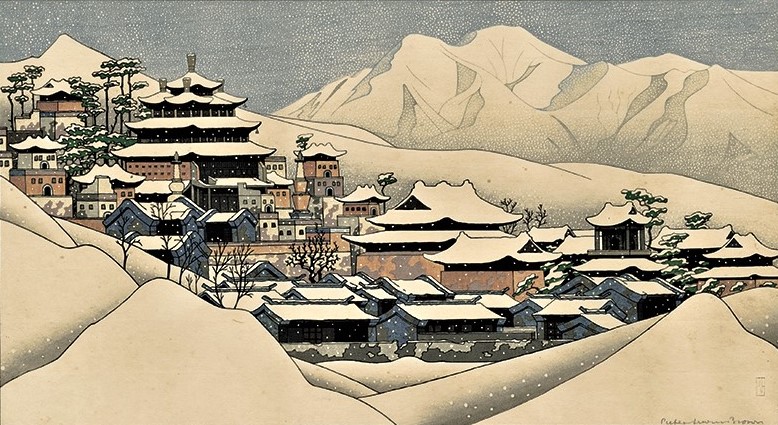

First a watercolourist (hundreds produced in a few years), he chose from 1934 the technique of wood engraving as his main means of expression and had the intelligence to surround himself with the best Japanese engravers and printers at that time (Kazuo Yamagishi, Kentaro Maeda, Tetsunosuke Honda) who quickly recognized in him one of the masters of ukiyo-e. Very early on, his prints were exhibited in Tokyo, Osaka, Kobe, Yokohama, Seoul and Honolulu. People discovered in his work a sharp sensitivity but also an almost ethnographic approach, a daring sensuality crowned with perfect technical mastery, a colourful world all in roundness and smile but saddened by the certainty of its near disappearance.

Japan's entry into the war at the end of 1941 abruptly interrupted his career. Isolated and affected by the growing chaos, he ceased his activities for the duration of the conflict. In order to avoid the bombardments, he was forced to take refuge in Karuizawa, a mountain village far from the capital, where he was placed under house arrest until the end of the war on August 15, 1945.

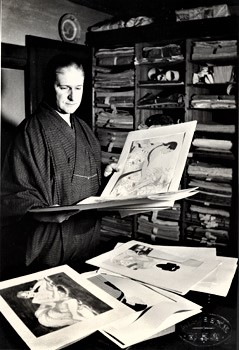

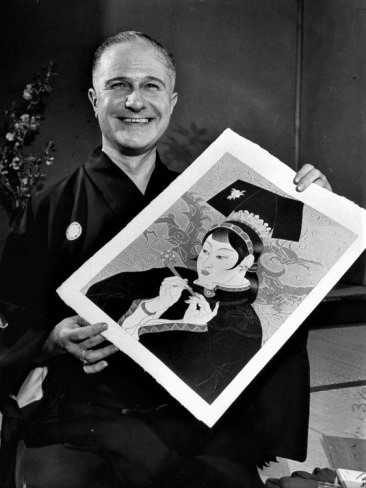

However, from 1946, encouraged by some American members of the occupation troops, he exhibited again in Tokyo, gratified by a visit from General Mac Arthur. He also resumed the production of new prints by bringing together his Japanese collaborators, engravers and printers, in Karuizawa. His success therefore went beyond Japan and Korea to extend to the United States where numerous exhibitions of his works were organized by his personal agent Michael Finkin. Among the buyers of his works, we can note President Harry Truman, Mac Arthur, Queen Juliana of the Netherlands, Marlène Dietrich, Edward G. Robinson... He visited different Japanese regions in search of new subjects of inspiration for portraits always imbued with the same humanity. At the end of 1954, he undertook a trip around the world, passing through Hong Kong, Singapore, Australia, New Caledonia, Tahiti, Panama, Martinique but was refused a visa for the United States, then plunged into McCarthyism. Almost no work came out of this long journey, as if only Asia inspired the artist. Despite the deterioration of his health due to diabetes, he continued to create new prints from watercolours he had painted sometimes many years ago. The last, La tragédienne, Mandchoukuo, is dated January 1960. He died on March 9 in his house in Karuizawa and is buried in the cemetery of Aoyama in Tokyo.

Acquired by numerous American museums, his works have been exhibited there for more than sixty years now. Paradoxically, Paul Jacoulet remained completely unknown for a long time in Europe and especially in his country of origin. It was not until 2011 that a first exhibition was held at the National Library of France. The consecration came in 2013 thanks to the brilliant event organized by the Musée du Quai Branly in Paris (the name of the exhibition was "A traveling artist in Micronesia, the Floating Universe of Paul Jacoulet"), the museum to which his adopted daughter Thérèse donated all the works that she owned, more than two thousand pieces from her father, mainly watercolours. Finally, I organized myself the exhibition of a hundred of his prints with the help of La Maison de la culture du Japon in Paris in 2016.

Why is the importance of Jacoulet recognized today ? He appears both as a spectacular heir to Japanese painting and accepted as such by the Japanese; and as one of the rare Western painters to have chosen to describe the diversity and richness of civilizations by offering us a flamboyant series of portraits of men and women from the countries of the Far East and of the Pacific archipelagos. He learned to perfectly master the techniques of wood engraving, while entrusting their manufacture to Japanese craftsmen, but never simply copied the great masters he loved so much. He was also able to go beyond the exoticism of his subjects to magnify by line and colour a humanity that he wanted to be beautiful. This search for Beauty in Diversity is the mark of great rigor, extreme sensitivity, deep intelligence and immense respect for the Other. It makes Paul Jacoulet a true precursor of contemporary thought and art, on a par with Paul Gauguin in Tahiti, Victor Segalen in Beijing or later Claude Lévi-Strauss and his “Tristes tropiques”.

Paul Jacoulet and wood engraving

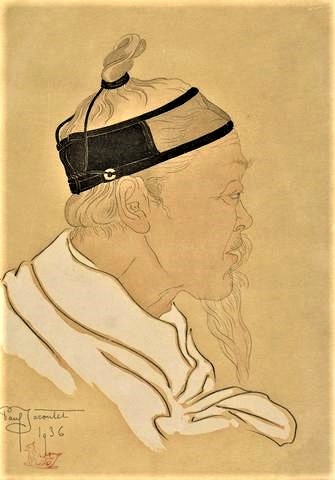

Paul Jacoulet was first a watercolourist whose prestigious collection of nearly 2,000 works is today at the Musée du Quai Branly in Paris. But his notoriety is mainly based on wonderful woodcuts where he used the traditional Japanese technique of printmaking by adding the precision of his line, the brilliance of his colours and the strength of each of the subjects presented.

A pencil drawing generally precedes the making of a watercolour with a precise line that prefigures the final work. The artist then takes a black and white photo of the watercolour from which he draws a very thin film, framed to the dimensions of the chosen wooden plate and on which he glues it. The engraver then creates a first matrix where the contours appear. Paul Jacoulet then composes the colours and indicates to the engraver the location of each of them. The engraver then executes the number of dies needed according to the number of colours. However, he can use the same matrix for non-neighboring areas of colour or for several shades of the same colour. The number of dies needed can be fifteen to thirty depending on the variety of colours. The process is further complicated by the frequent addition of mica, gold or silver threads, or by the addition of embossing. The wood used for the dies is cherry.

The printing is carried out by a highly specialized printer: it is done gradually by successive passages of the sheet on each of the dies. A print can thus require dozens of printing passages, sometimes more than fifty for the most complex works. Paul Jacoulet uses his own paper, which he specially brings from Fukui and on which his initials “PJ” appear transparently. Actual print runs were usually 50 to 150 copies.

For more than 30 years, a faithful group of 7 engravers and printers participated in the making of the work, including the most famous engraver of this period, Kentaro Maeda. In the margin of each print are the stamps of the engraver and of the printer and on the print itself appears the magnificent and large signature of Paul Jacoulet which always accompanies one of the seals created by the Master. 17 different seals have been identified and correspond to series or periods. From 1934 to 1960, Paul Jacoulet made a total of 162 prints, almost all of which were 39 x 26 cm Oban. There are also four smaller Surimono (15 x 10 cm), created for commemorations.

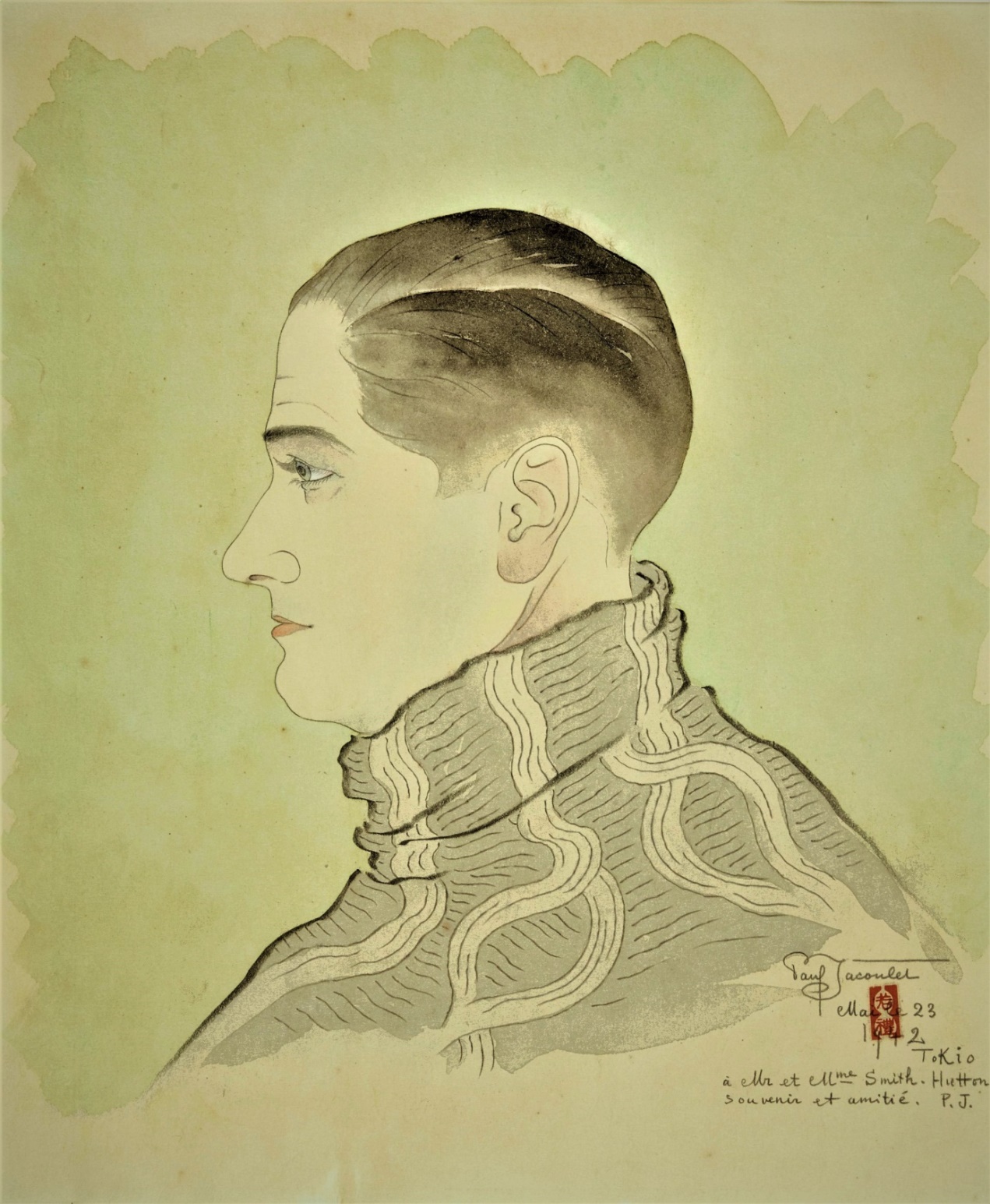

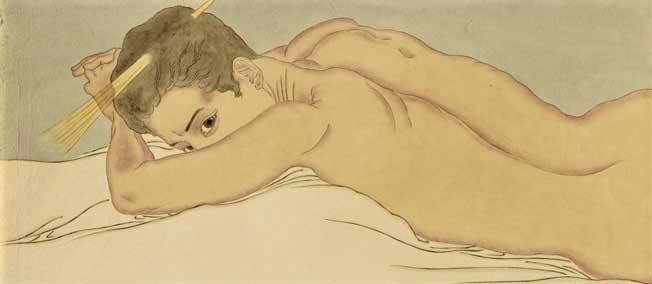

Paul Jacoulet and watercolours

Given the print runs (usually between 30 and 150), Paul Jacoulet is best known for his prints. But he is also an exceptional watercolourist. The number of these works is estimated at nearly 2,000, some made between 1911 and 1928 (there are two examples below which show that Jacoulet was very "Japanese" at the time), but most of them between 1929 and 1949, period when the unique style of the artist asserts itself. A selection of 700 watercolours is presented in the catalog of the 2013 exhibition at the Musée du Quai Branly in Paris. Many were made in situ during travels, notably in Micronesia and Korea. They are very elaborate and most offer portraits full of tenderness of people encountered. 166 watercolours gave rise to woodcuts.

Watercolours are very rare on the market and of high prices and therefore none are unfortunately in my collection. However, below are some pictures of rarely presented watercolours.

Bibliography :

- Paul Jacoulet wood-block artist, by Florence Wells, Foreign Affairs Association of Japan, Tokyo, 1957

- Paul Jacoulet, Rainbow of colour, by Steward Teaze, manuscript non publié, 1961

- The prints of Paul Jacoulet by Richard Miles, Pacific Asia Museum, Pasadena, 1982

- Watercolours of Paul Jacoulet, by Richard Miles, Pacific Asia Museum, Pasadena, 1989

- Paul Jacoulet, by Kiyoko Sawatari et Chistian Polak, Yokohama Museum of Art, Yokohama, 2003

- Paul Jacoulet’s Vision of Micronesia, by Don Rubinstein, ISLA Center for the Arts, University of Guam, 2007

- Un artiste voyageur en Micronésie, L’univers flottant de Paul Jacoulet, sous la direction de Christian Polak et de Kiyoko Sawatari, Musée du Quai Branly, Paris, 2013