LILIAN MAY MILLER (1895-1943)

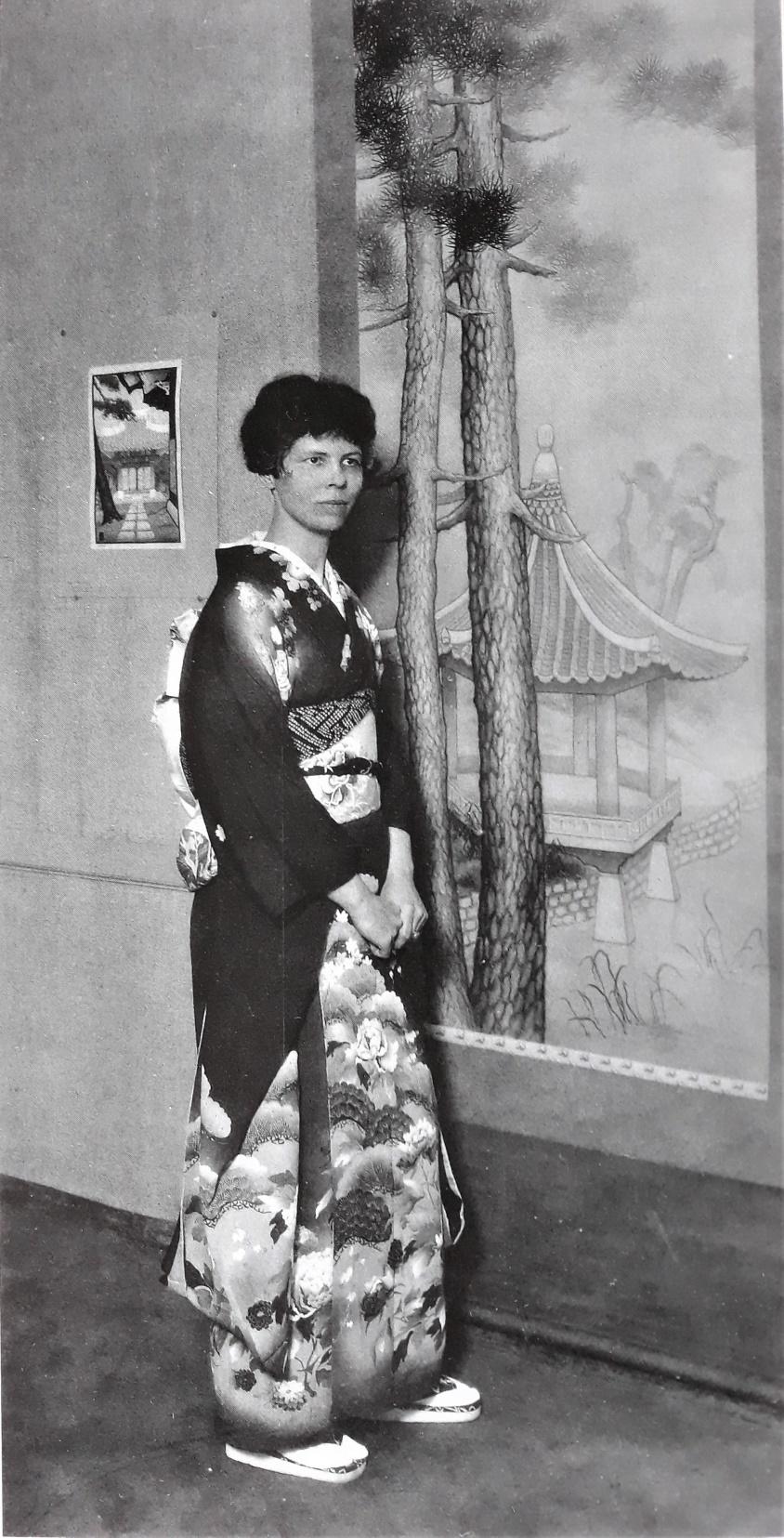

Lilian May Miller, daughter of an American diplomat, born in Japan where she spent most of her life, was both Western and Far Eastern, linking the two cultures. She called herself "Jack" and often took herself for a boy, here also looking for a double identity. This complex personality and especially the mastery she shows in her art make her one of the richest personalities of the Far Eastern school.

Her father had just been appointed to the United States Embassy in Tokyo when she was born there in 1895. He remained there for 15 years, becoming one of the best specialists of the Japanese empire. Lilian Miller therefore spent her entire childhood there and cultivated a real intimacy with Japanese culture like, at the same time, Paul Jacoulet. She approached painting from the age of 9 by following the courses of a painter, Kano Tomonubu (1843-1912) that her elders Charles Wirgam, Emil Orlik and Ernest Fenollosa had attended before her. In 1907, she choose as a master the specialist in historical representations Shimada Bokusen (1867-1941), who helped her exhibit for the first time. She also met Helen Hyde, probably in Nikko where they both spent the summers. They will remain friends. However, she must leave Tokyo following the appointment of her father in Washington.

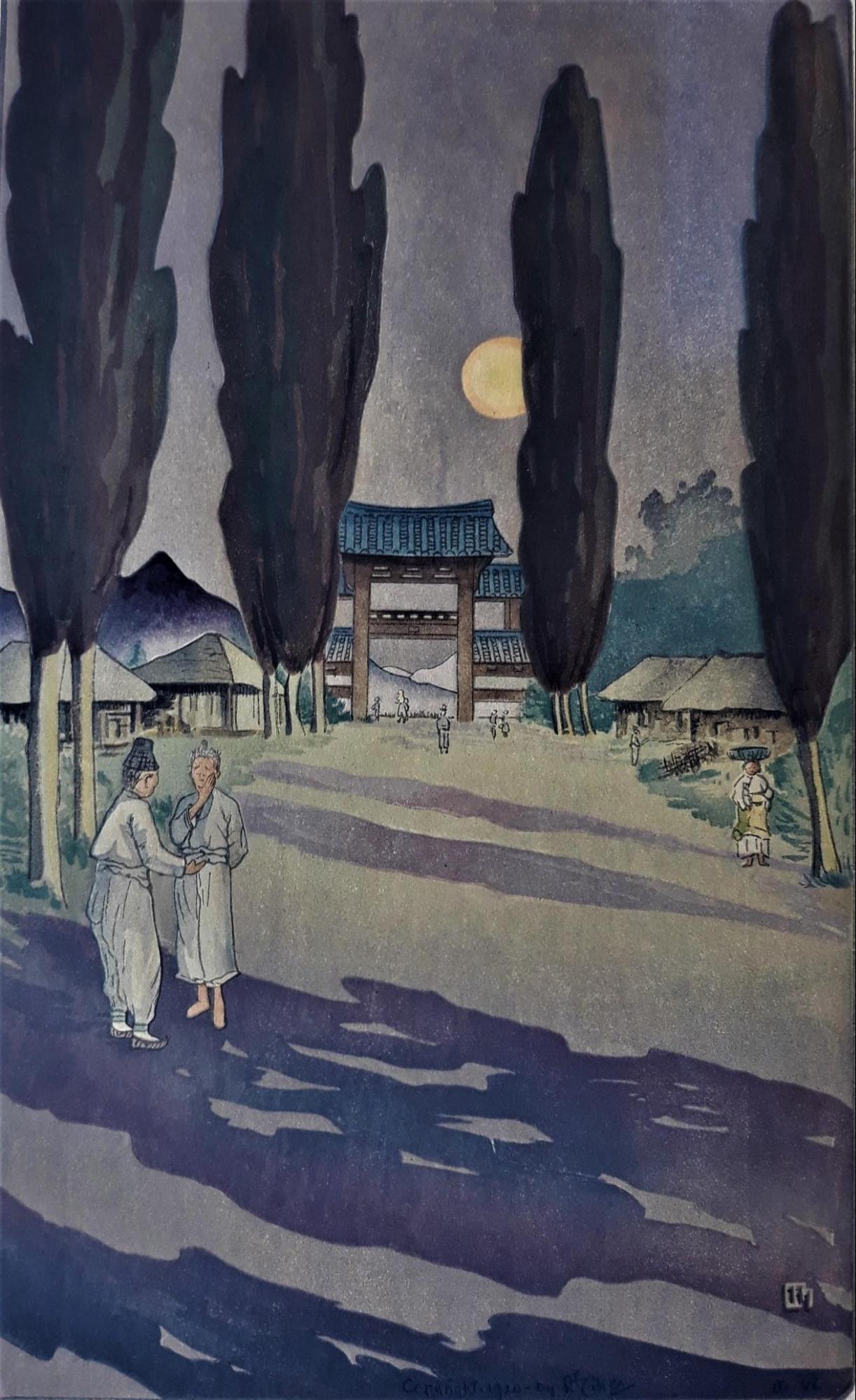

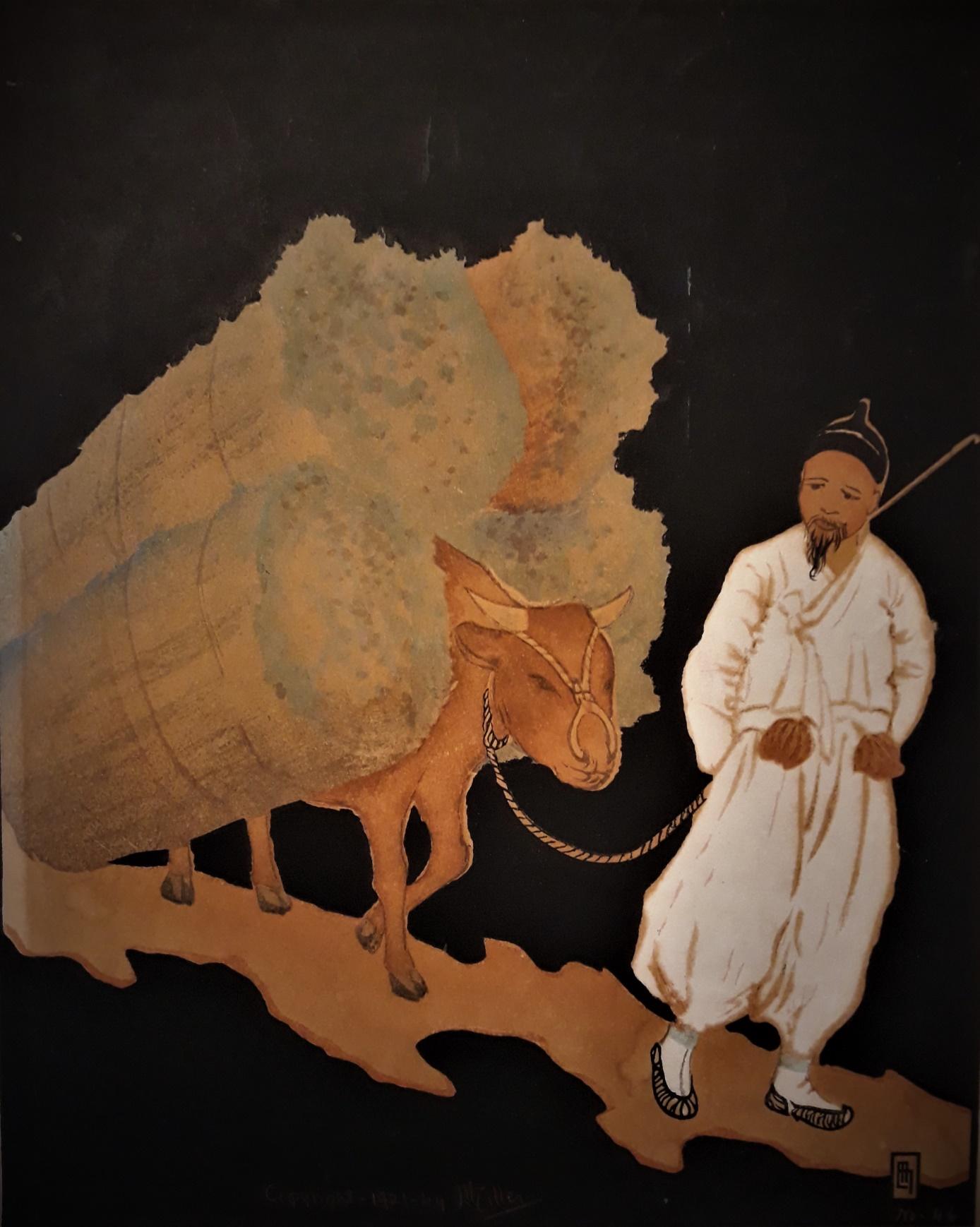

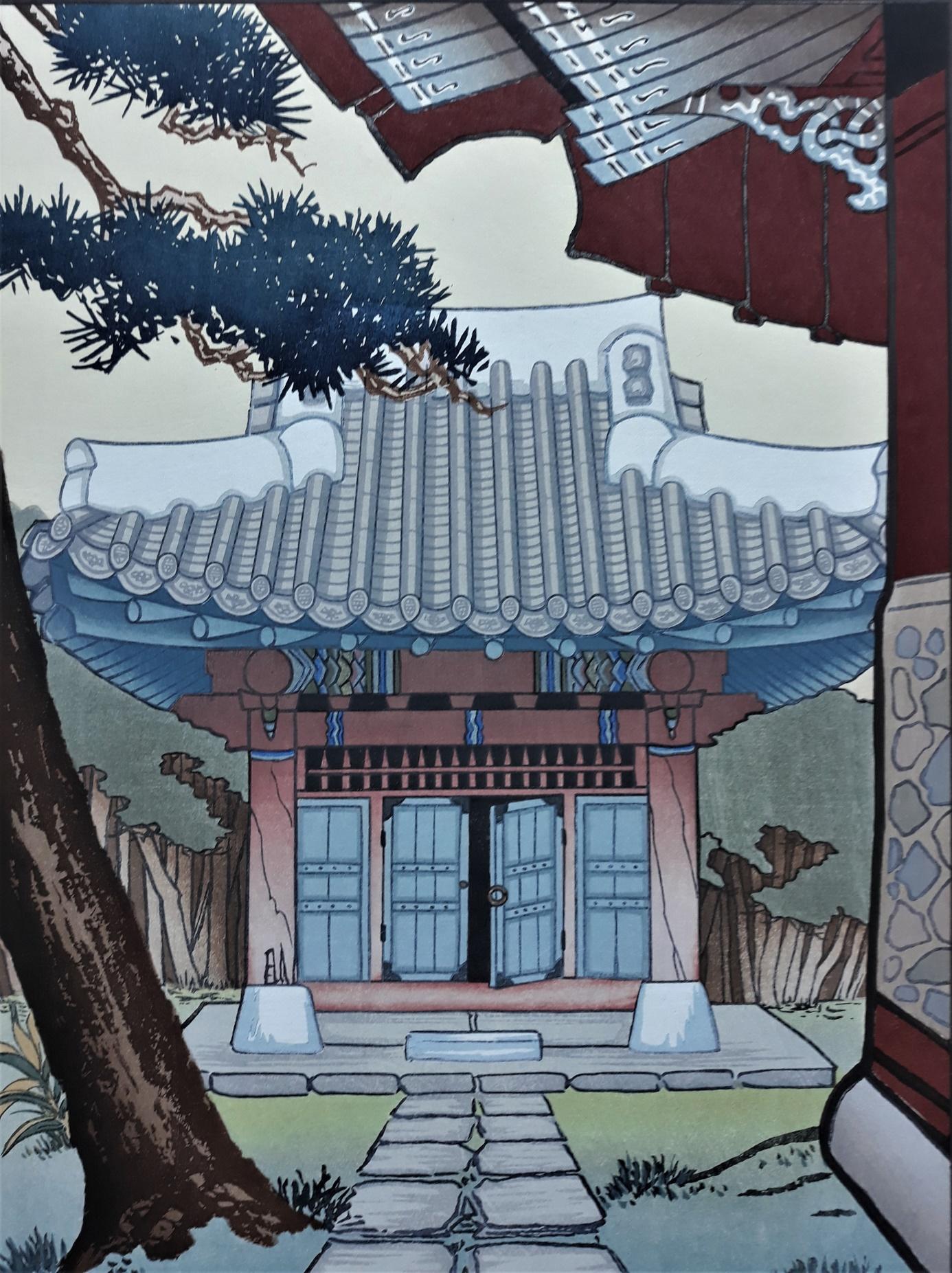

In 1913, she enrolled at Vassar College, a prestigious arts college near New York. There she befriended Edna Saint Vincent Millay, a poetess very free in morals for her time and whose bisexuality must have impressed her. After completing her studies, she joined her father in Seoul in 1918 where he was consul general and spent almost a year there discovering Korean culture, which was to play an important role in her work. But it is in Japan that she ended up settling.

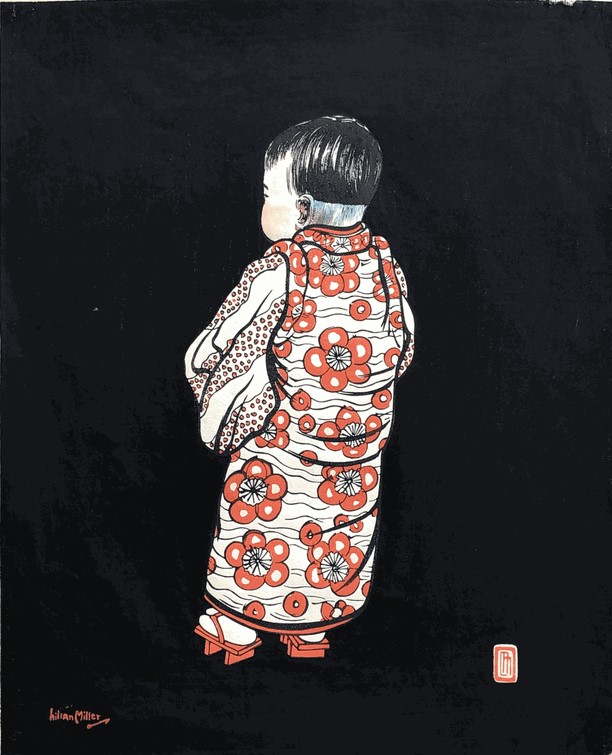

Very quickly, she forged contacts with artists who then relaunched the Shin-Hanga movement and in particular with the engraver Matsumoto and the printer Nishima Kumakichi II (he had already worked with Bertha Lum and so it is very likely that the two women met). She learned quickly and was appreciated by the masters of Ukiyo-e of the time, amazed by the precocious talents of this young Westerner speaking and living in the Japanese way. Her success was also commercial because she then produced hundreds of greeting cards whose subjects were mainly Korean. She sold them both in Asia and in the United States which discovered this American woman who introduced them a human Asia, far from a lot of caricatures. Many of her subjects were portraits of women, children or old people, thus joining the feminine approach of Helen Hyde. But she was also already creating marvelous prints that herald a major work.

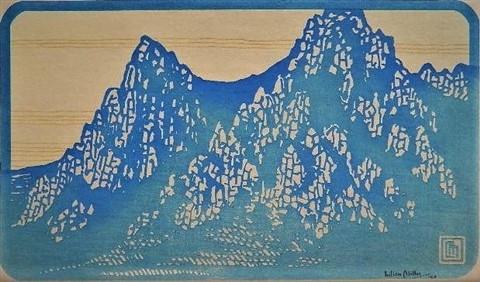

This success was brutally interrupted by the earthquake that struck Tokyo in 1923. She was unscathed but lost her house and all the works that were stored there, wooden blocks like engravings. Deeply affected and seriously ill, she took refuge for 3 years with her parents in Seoul, slowly resuming her creations. It was through the publication in 1927 of a book of poetry that she reappeared in Japan, Grass blades from a cinnamon garden, beautifully illustrated. She also made the decision to now produce her woodcuts alone, assuming all the stages, drawing or initial watercolour, carving woodblocks, engraving and printing. She was the only Western artist to make this choice, the others, like the majority of Japanese artists, preferring to entrust the engraving and printing to famous local craftsmen who also helped them to market their works. In 2 years, she managed alone to create about thirty prints which are the most beautiful success of the dialogue that she wanted between the West and the East.

On the strength of this exceptional creation, she decided in 1930 to make an extensive tour of the United States to make herself better known. Boston, Washington, Philadelphia, Chicago, New York, Kansas City, Denver, Pasadena, everywhere she received a warm welcome. A fashionable artist, she sold her works to high society, notably to President Herbert Hoover's wife and to Abby Aldrich, wife of the wealthy John D. Rockefeller Jr. But she also became friend with American feminists of the time and especially with the influential gallerist Grace Nicholson who for several years has been a passionate friend… but distant.

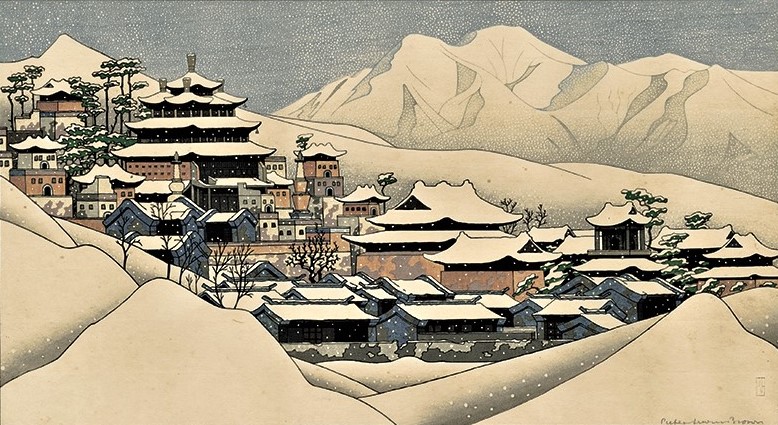

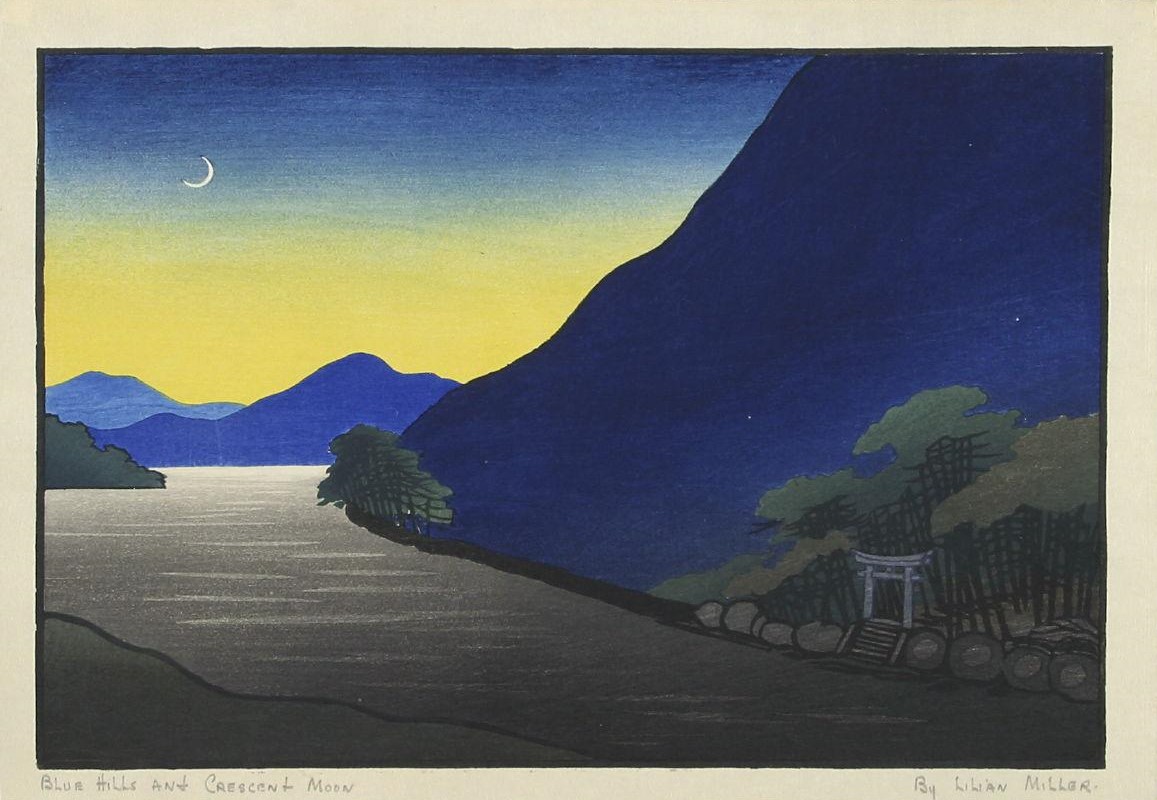

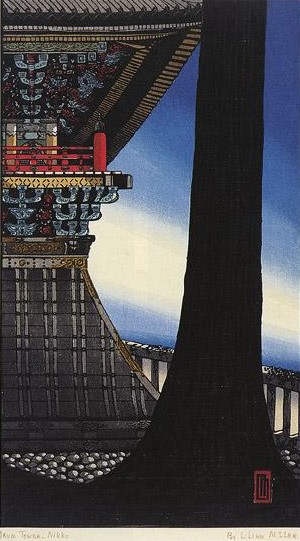

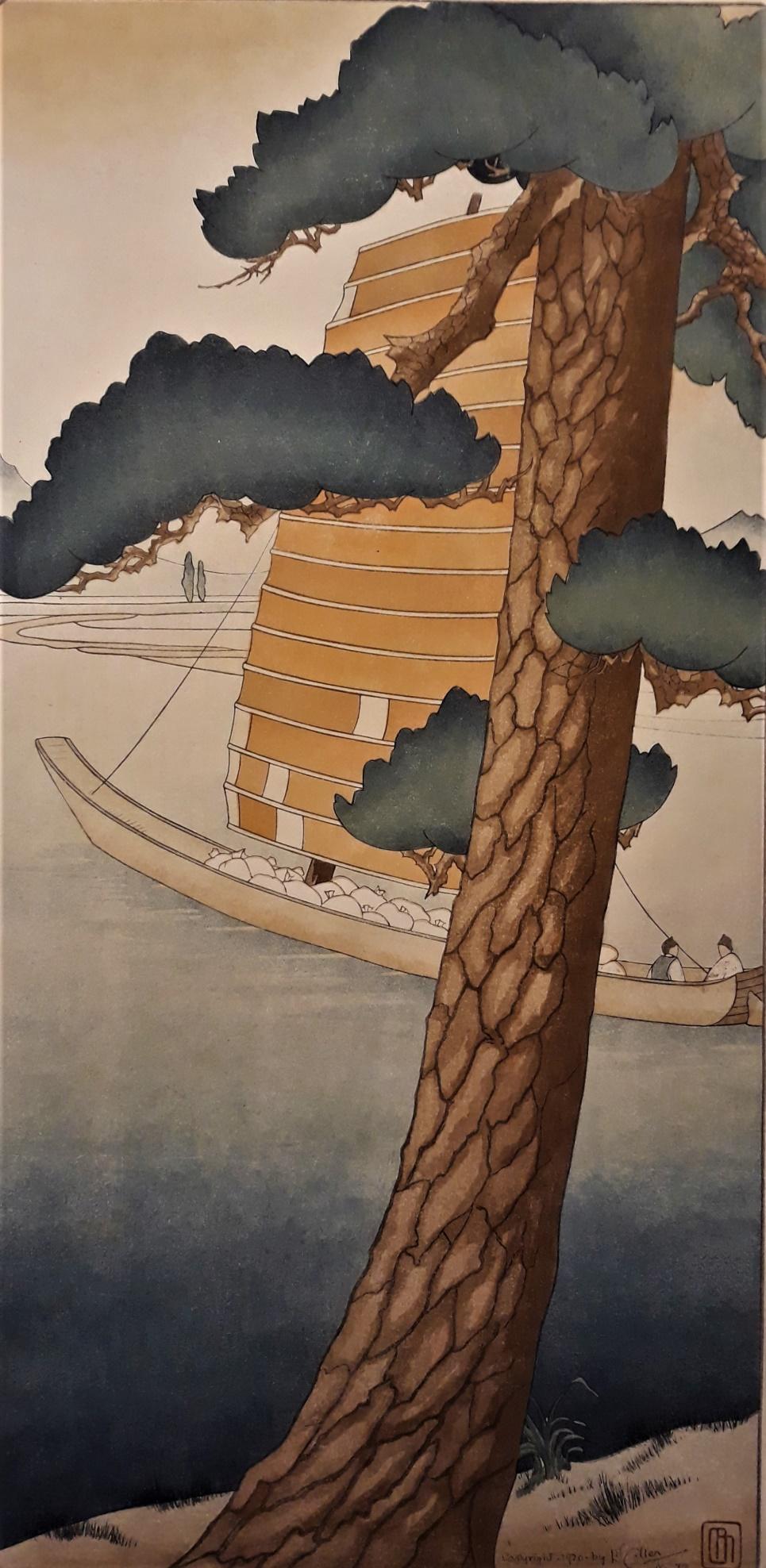

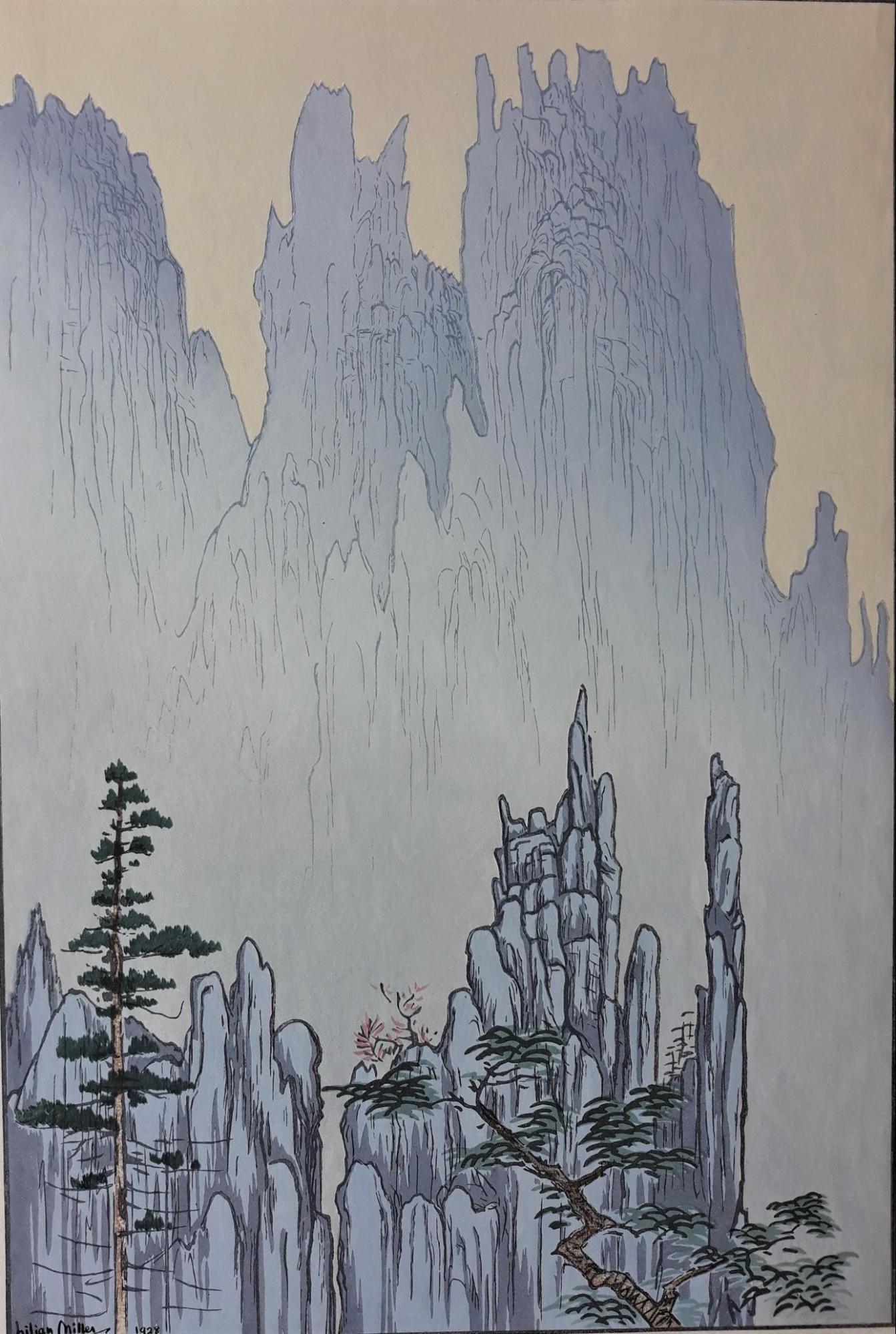

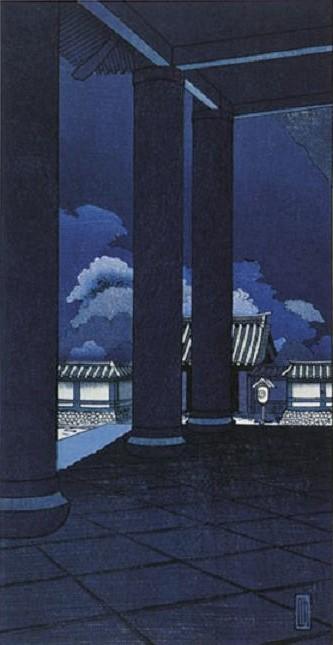

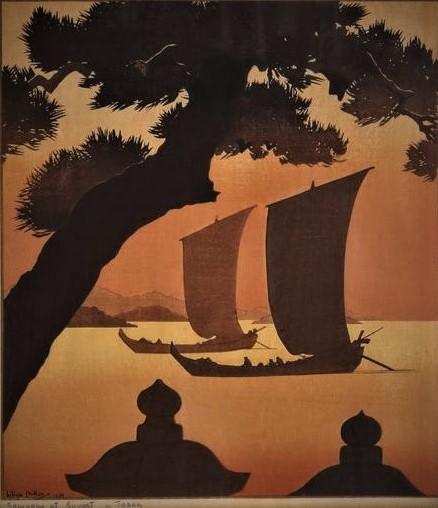

Because despite this reciprocal affection, at the end of 1930, Lilian Miller returned to Japan and spent a last stay there for 5 years, “without a fixed address”, passing from Tokyo, to Kyoto, Nikko, or Kamakura. During that period, her production remains intense and oriented towards the representation of sumptuous landscapes, refined, in warm colors, where the deep blue of the nights combines with the yellow setting sun or the lunar brilliance, and where the pillars of the temples and the trunks century-old trees compete in audacity towards twilight skies. She was recognized by the best Japanese artists as one of their own, and the diplomatic community in Japan enthusiastically acquired her creations. Her displayed biculturalism was then compared to those of the painter Léonard Foujita who then was winning a great success in Europe and of the sculptor Isamu Nogushi celebrated in the United States.

Lilian Miller's life changed dramatically in 1935 : she was operated on for a serious cancerous tumor which weakened her for a long time. And in February 1936, a bloody coup attempt by part of the imperial army broke out in Tokyo. Miller no longer recognized "her Japan" in the growing nationalist drift that affected the whole country and she decided to break with her adopted nation. Accompanied by her mother, she moved to Hawaii and found a haven of peace there for 2 years. But she had to give up wood engraving, a technique that had become too heavy for her, and she then devoted herself to watercolour, ink painting and lithography. Landscapes like colours were rare but the inks of marvelous bamboos always display her orientalism. She was quickly adopted by the Hawaiian community and received the support of the wealthy Rice-Cook family, like, at the same time, the painter Charles W. Bartlett whom she surely met.

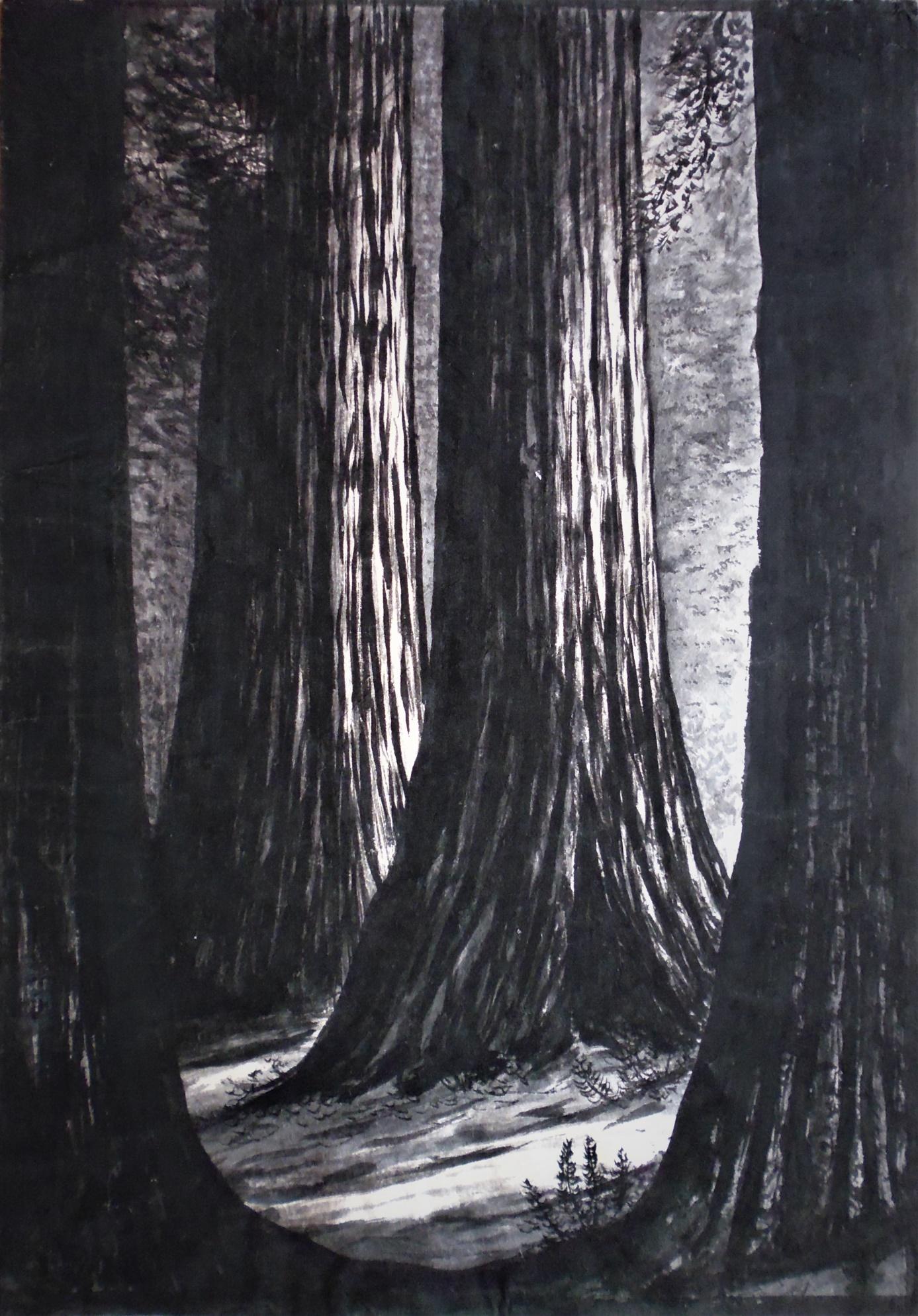

Mother and daughter left Honolulu at the end of 1938 for a definitive return to the United States. Lilian Miller still found in the massive trunks of the cedars and redwoods of California the memory of the Japanese landscapes that she loved so much, but the colours gradually disappear to give way to still lifes in dark hues. Her world collapsed irreparably on December 7, 1941 with the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. She experienced the event as a real betrayal of the ideals that had structured her whole life. The Japanese half of herself sank with the American fleet and her biculturalism was no longer possible. She abandoned her brushes and would have even destroyed all her remaining works without the intervention of her friends. For a whole year, she devoted herself to her homeland by enlisting in the US Navy, in charge of translation and information services. Cancer caught up with her and she died on January 11, 1943. She was only 47 years old.

Lilian May Miller is perhaps the most representative personality of this complex artistic movement that was Far Orientalism : an attempt to live a double cultural identity in order to find the necessary resources for creations that went far beyond the western origins of the artist. She also had to live her femininity, like all the other female representatives of the movement, at a time when it was difficult for a woman to assert herself. Assuming her posture of “tomboy”, she never married, had no children and favored female friendships. She has constantly sought full independence, both artistic and financial, and she is a unique case of mastery by a Western artist of all the stages of wood engraving. Recognized during her lifetime for her original creation as much by her compatriots as by the Japanese masters, consecrated as a bicultural artist, her notoriety after the war suffered from the discredit affecting Japan. A few decades later, her work is again placed among the most successful of the Far Eastern movement.

Bibliography :

- Between two worlds, The Life and Art of Lilian May Miller, by Kendall H.Brown, Pacific Asia Museum, 1998

- Grass blades from a cinnamon garden, by Lilian May Miller, Japan advertiser press, Tokyo, 1927

The collection

One of the very last works of Lilian May Miller…